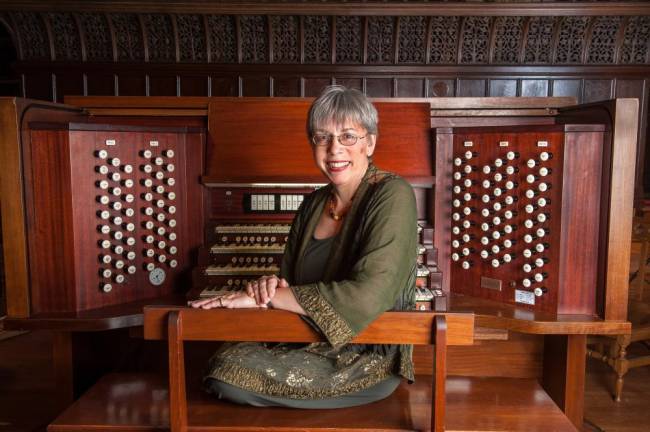

Gail Archer has performed on almost every organ in the city and countless others in the United States and Europe. “It’s not like being a violinist where you bring your instrument with you,” the world-renowned concert organist, who plays up to 50 concerts a year nationally and abroad, explained. “All the instruments are different, so you have to adapt yourself to what you find when you arrive.”

A Patterson, New Jersey native, Archer began playing the organ at age 13 after singing in her church’s choir. In 1985, she moved to the Upper West Side, where she’s lived ever since, making a name for herself in the New York arts arena. She has served as the director of the music program at Barnard College since 1988, where she conducts the Barnard-Columbia Chorus and Chamber Singers and teaches music history, and is also the college organist at Vassar College.

Through her musical travels, Archer developed a penchant for the organ culture in Eastern Europe and has worked to promote it in Western Europe and the United States. The Harriman Institute at Columbia University took notice and elected her to join its faculty in 2017. In fact, it is this academic institution committed to Russian, Eurasian and East European education, that will be co-sponsoring Archer’s upcoming trio of Polish, Ukrainian and Russian concerts at three Manhattan Catholic parishes, the Church of St. Francis Xavier, St. Jean Baptiste Church and St. John Nepomucene.

During the pandemic, she is quite busy, working at both universities, releasing a Ukrainian-inspired CD, learning Russian and preparing for her upcoming concerts — which will be held in February, March and April to limited, first-come, first-served audiences in keeping with COVID precautions.

How has your role at Barnard-Columbia changed with COVID?

I’m in charge of the vocal program for the whole university — the voice lessons, the voice classes, the opera. I also am the academic advisor to all of the music majors and I advise first and second-year students who haven’t declared their major yet, but have interest in music. I’ve had maybe 3,500 choristers over all these years, about 100 a year. My role is the same, but the choir is virtual. The students are simply singing wherever they are and we have the piano, and they can hear that. And we just have sung through a great deal of literature last semester and this semester. Actually, a lot more music than we would do, because we’re reading through, since we can’t have a performance with everyone. Typically, there are 80 people in the Barnard-Columbia chorus — undergraduate, graduate students, faculty, alumni. It’s a wonderfully diverse group. And that’s still the case, but we’re just a lot smaller as we’ve gone virtual. We’re maybe 35, because not everyone wants to sing virtually. And then I have the chamber singers, and that’s about the same size, about 15 singers. So actually nothing has changed; I still direct the two choirs. I still teach music history at Barnard virtually.

What is your role at Vassar?

I’m college organist. I got that position in 2007 and started out with just a handful of students, but now, after 14 years, I typically have 12 to 15 organ students all the time. So the program has grown and we’ll have three or four students graduate, but then I’ll recruit and we’ll have new students in the first-year class. I’ve been teaching them in person this last semester, just going to Vassar on Fridays. And they’re going to start in person again in February and will go through to June.

Every summer, you embark on a European tour. Did you ever experience any mishaps where you sat at the organ and something was amiss?

I remember the first time I played in Russia, in 2013. My colleague in St. Petersburg has received a grant from the Russian government to invite organists to play all over Russia before the Sochi Olympics, in 2014. So there were dance companies, theater companies, musicians, who were invited to Russia in the summer of 2013 leading up to the Olympics. The first place I played was Irkutsk, which is way out in Siberia. It was the furthest from home I have ever been. And I went to the organ hall, and it was a rolltop desk arrangement, where you had to lift up the cover of the organ in order to practice. And I’m thinking, “I don’t read a single word in Cyrillic. What if all the stops have Cyrillic names on them and I don’t know what any of this means?” And I lifted the desktop and heavens above, there were traditional German names on all the stops and I just said, “Oh Hallelujah!” But since then, I am learning to speak Russian. I’m in the third-year Russian course. In fact, I had a Russian lesson today. I’m learning to read, speak and write. It’s been fascinating.

Tell us about the network for women organists that you founded in 2013.

In my travels, I heard stories from my women colleagues about women having a difficult time making professional progress in the field. They were passed over for promotion or in the application process and treated unkindly in the workplace when they succeeded. And I had some disappointments in some New York institutions myself, so I decided that we would band together to support one another. So I did research on women organists across the country and published that. And as I’m speaking to you today, there are no women leading a conservatory organ program in North America. There is one woman who is teaching organ at a research university in a major city, in Phoenix, Arizona. Then there are two women who are cathedral musicians in a major city in the United States. One here in New York, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and one in Houston, Texas, at the Catholic cathedral there. Women can’t even apply for the positions because they’re often filled before they’re even announced. So I started Musforum, which means “music forum,” but it also means “muses,” the ancient Greek goddesses of the arts. And every two years we’ve had a conference; the first one was in 2015, here in New York.

For your Slavic concert series, will there be audiences in the churches?

Yes, people are allowed to come. They will have to be socially distanced, but all three concerts are free and open to the public. The first concert will be all contemporary Polish composers for the organ. The oldest music comes from a gentleman named Surzynski; he died in 1924. This program starts with music from the late 19th century and includes music by a living composer, Pawel Lukaszewski. And I always try to include music by a woman composer, so I have “Esquisse for Organ” by Grazyna Bacewicz ...The Ukrainian program is the exact same one that is on my CD, which was just released in September. That has contemporary music also. The oldest piece is by a gentleman who passed away in 1924. A living composer, my colleague Bohdan Kotyuk, has several pieces on that program. And there’s a piece on that program by a woman too, Svitlana Ostrova. And she’s living; she was born in 1961. So it’s wonderful to play music by living composers. And finally, the Russian program was also from my CD.

www.gailarcher.com