City Powerless to Seize Buildings from Landlords Who Fail to Pay Property Tax Bills Due to COVID Era Law

A law meant to protect small homeowners from losing their homes during the worst of the pandemic, has stripped the city of ability to use tax liens to seize properties from deadbeat landlords. One City Council member is pushing a bill to put teeth back into property tax laws.

A policy change meant to save low-income homeowners from losing their homes during the worst days of the pandemic has tied the city’s hands when it comes to ensuring people pay their property taxes, experts say.

“The truth is that without a lien sale there is very little the City can do easily to collect unpaid taxes,” Ana Champeny, vice president of research at the Citizens Budget Commission, told Straus News. But experts say some big multi-home landlords are deliberately flaunting the law and not paying taxes.

In one example, the owner of 131 West 70th Street, a five-story brownstone listed by the Department of Finance as a one-family home, owes the city roughly a quarter of a million dollars in unpaid taxes on the property going back at least until 2019, according to public records.

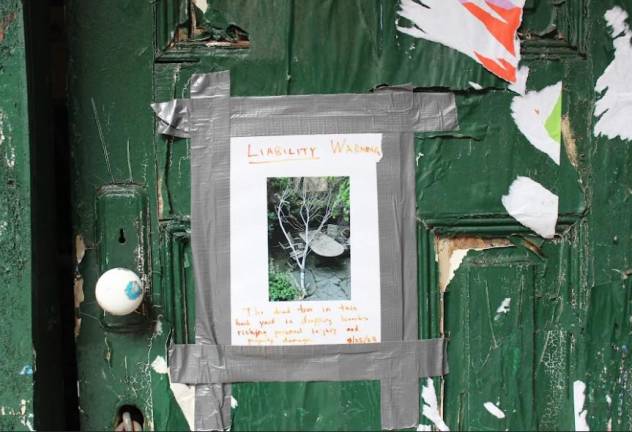

Unlike the types of owner-occupied buildings the Council sought to spare when it ended the lien sale, the building is empty, boarded up and racking up violations.

“It is outrageous that the owner, whomever he or she is, can just keep this building like this and not pay taxes and nobody can do anything,” said City Council Member Gale Brewer who represents the upper West Side in an interview.

The building’s owner, Buttercup Management Corp., is registered at a nearby West 75th Street address. According to city records reviewed by Straus News, that is also the headquarters of P.V.P. Management Corp., which owns five properties on East 6th Street, and Cabe Management Corp., which owns the West 75th Street property.

A spokesperson for Buttercup Management, Charles Campos, is listed in the records as the president of all three corporations. His Manhattan portfolio is valued at upwards of $30 million.

Reached in his basement office on West 75th Street, Campos said he was the “victim” of an unfair campaign by Brewer, whose office had not contacted him directly about his unpaid taxes. “Many people have unpaid taxes. It’s not different from many other [buildings],” he said. “Why pick on mine?”

The end of tax lien sales—the sale of unpaid property tax debt to collectors—has left the city with few tools to enforce its property tax code, which accounts for roughly one-third of city revenue.

According to Champeny, the budget analyst, the issue is broader than missing collection mechanisms. The tax code itself is not calibrated to mitigate the pressure on owners that comes from New York’s steep housing market, she said.

While the City Council let the power expire in 2021 in order to protect small-homeowners on fixed incomes, larger landlords may be taking advantage of the lax enforcement. One fiscal watchdog said the end of the tax lien sale leaves the city no avenue to quickly recoup property taxes, forcing it to turn a blind eye to delinquent landlords or initiate lengthy foreclosure proceedings that cost money and ultimately leave the city responsible for the upkeep of property. According to a report by The Real Deal, first year delinquencies increased from $587 million to $735 million between fiscal year 2022 and 2023.

“The process of foreclosing on a property takes time and is not necessarily the action the City wants to take; it wants to collect the back taxes,” said Champeney. “And the City’s experience of owning in-rem housing stock [homes that were repossesed by the city] in the 1980s and 1990s demonstrated that the City is not the best candidate to be a landlord,” she said

When asked what type of enforcement power the city had in lieu of lien sales, a Department of Finance spokesperson didn’t point to any, telling Straus News the administration was searching for a legislative fix. “The Department of Finance is working to overhaul property tax enforcement to protect vulnerable homeowners from losing their homes and preserve community affordable housing assets while ensuring that everyone meets their fundamental civic obligations,” the spokesperson wrote in an email statement. “We will continue to work with the City Council and all stakeholders to pass legislation this year.”

A bill moving through the City Council could give the city new tools to recoup unpaid property taxes, according to its supporters. The legislation would establish a public land bank that its sponsor, Council Member Brewer, said will give the city the power to retain land of tax-delinquent owners, using a nonprofit to structure the terms of future action. The bill, which has the support of a majority of the Council, was heard in committee earlier this year but hasn’t come to a vote.

Brewer sees the building on 131 to W. 70th St. and its back tax bill of over $250,000, as representative of the larger problem the legislation aims to address.

According to Champeny, the budget analyst, the issue is broader than missing collection mechanisms. The tax code itself is not calibrated to mitigate the pressure on owners that comes from New York’s steep housing market, she said.

“The more fundamental problem is that for some homeowners their property taxes have become unaffordable and the city should look to directly address that financial challenge rather than simply allowing these owners to accumulate extensive property tax debt that ultimately they or their family members will have to resolve,” Champeny said.