Could Vaccine Tourism Spark NYC’s Recovery?

The emerging surplus of shots starts talk about how to speed an economic comeback

The phrase “vaccine tourism” rings ethical alarms, conjuring visions of wealthy entrepreneurs decamping to Gulf emirates and privileged snowbirds scrambling across the Florida state line for their jabs.

Mostly, it has been something happening somewhere else on the down-low.

But the emerging surplus of vaccine in the United States is encouraging a new conversation about vaccine tourism as a tool to speed the recovery of New York City’s economy.

Other travel-dependent locations are already doing this. The US Virgin Islands has been quietly vaccinating tourists this winter, using doses they said were surplus because some of their own residents were hesitant to take them.

In Alaska, with their crucial summer tourism season approaching, the state last week solicited proposals to inoculate arrivals at major airports. Craig Offman, a Canadian journalist in Toronto, wrote in the Wall Street Journal this week that he and his mother had counted “40 people we know who had migrated south over the past two months in search of shots.”

So the issue isn’t whether people will travel to get vaccinated. “It’s inevitable,” says Peter Greenberg, travel editor of CBS News. For New York, the question is whether the city, whose economy is heavily dependent on travelers, should embrace “vaccine tourism” and manage it safely?

“First and foremost I’d like to see all New Yorkers and Americans, including kids, vaccinated,” said Cristyne Nicholas, the public relations exec and former CEO of NYC &Co, which promotes travel to New York. “Then, if there is a glut of vaccines for use in the United States, it may make sense to do what some other tourism-centric nations are doing, and vaccinate visitors to prevent virus spread and help put NYC’s more than 403,000 tourism and hospitality employees back to work.”

Equity Challenge

The distribution of COVID-19 vaccine has created one of the greatest equity challenges in history. While a few countries have vaccinated half or more of their population, other nations have yet to receive a single dose.

Seen against that challenge, vaccine tourism may come across as the rich helping the rich. On the other hand, a plan to help revive New York’s travel and tourism industry will benefit some of the city’s lower wage workers, who are disproportionately black and Hispanic and have been hardest hit by both the health and economic downturn.

This conversation is only moving center stage (as they would say in one of New York’s most travel-dependent industries) because the United States is facing its first happy challenge of the pandemic: how to use its impending excess supply of vaccine.

President Biden says there will soon be enough vaccine for every willing adult. In fact, the country has enough vaccine on the way to immunize every American, kids included, more than twice over.

Much of the rest of the world, in the meantime, remains desperately short, including Canada and Europe, which before 2020 were among the top sources of international tourist and business visitors to New York City.

Travel and Tourism

New York’s economy is so large and sprawling that New Yorkers themselves often underestimate the importance of travel and tourism. The pandemic offered a painful reminder as travel-dependent jobs evaporated in hotels, theatre, restaurants, conferences, museums, sports and entertainment.

In 2019 some 66.6 million travelers visited New York, a number chopped by two-thirds in 2020, to 22.9 million visitors. Most severe was the collapse of travel from outside the United States, which fell 82%, from 13.5 million visitors in 2019 to 2.4 million last year.

While international visitors were only 20% of total visitors before the pandemic, they stayed longer and therefore accounted for half of total spending by visitors, according to NYC&Co.

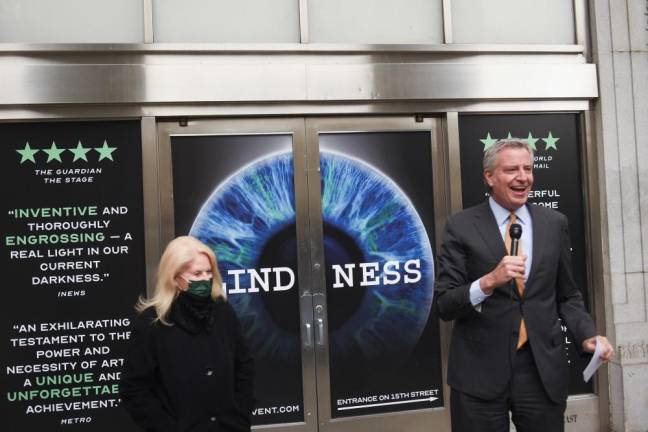

Mayor Bill de Blasio noted on Friday that the city’s cultural community accounted for more than $100 billion in economic activity. He observed this just before curtain time for the first play to open here since the pandemic. The play is “Blindness,” the tale of a community that survives a pandemic. “This is one of the moments that really signals to people our comeback,” the mayor said.

But for theater and other entertainment and culture to truly come back economically will require the return of international visitors. The Theatre League says that before the pandemic nearly one Broadway ticket in five was purchased by an international traveler. Similarly, Visa, the credit card company, reports that 20 percent of all spending on Visa cards in Times Square was by international visitors. Citywide, seven percent of all transactions on Visa cards, some $2.8 billion, was by international visitors. The figures don’t separate those who came on business and those who are vacationing.

“Economic Engine”

Travel to the United States, Nicholas notes, is the economic equivalent of an export, bringing in money that can be “the economic engine that will rebuild the economy.” Unaided, international travel to New York City probably won’t return to pre-pandemic levels until 2024 or beyond, according to estimates by NYC&Co.

So reviving this international travel more quickly would be the focus of a program to “come get vaccinated and enjoy New York,” both because international visitors are disproportionately important economically and domestic travel seems to be slowly reviving on its own. In any case, the coming vaccine surplus covers the entire United States so domestic travelers won’t have reason to come here.

Not so for others. Canada is a case in point. Pre-pandemic, an average of a million Canadians a year visited New York City. Offman noted that Canada’s vaccination rate of 1.8 percent trails Brazil. Reopening the US-Canada border would be a major economic recovery act for both countries.

The situation is particularly opportune for a vaccine tourism program because Canada, to stretch its vaccine supply, is delaying second vaccine doses for as much as four months. So an immediate opportunity would be to invite Canadians who have received their first dose to come to New York three weeks or a month later for their second dose.

That is pretty low risk, given the considerable protection provided by the first dose, particularly if travelers are tested and observe familiar mask and distancing protocols.

Gus Valenza, 66, lives in Toronto, where he is scheduled for his first jab Tuesday. His second dose, however, is not scheduled until the end of July because of Canada’s strategy to spread its thin supply.

He said he would be delighted to visit New York for his second dose, and see a daughter there whom he has not seen in a year. But he set one condition. He wants Ontario to drop its rule that returning Canadians have to pay for a three-day quarantine in a hotel picked by the government. Offman pointed out that this requirement is being challenged right now in an Ontario court as “overbroad, arbitrary and grossly disproportionate.”

New York can’t resolve that issue for Canadians. As for the rest, however, the city can do well for itself and good for its neighbor to the north by inviting Gus for a visit in May.