Looking at New York as a Work of Art

Lori Zimmer pays homage to all the fascinating “Art Hiding in New York”

After getting fired from her gallery job, Lori Zimmer finally had the time and purpose to explore the art that is all over Manhattan, in places like subway stations, parks, corporate lobbies, hotels and coffee shops, that as busy New Yorkers, we don’t always have the time to appreciate.

“I just really allowed myself the time to stop and look without having to rush off somewhere, and then go home and research it,” she explained of her initial art journey, which began in 2009 with an Excel spreadsheet and then turned into her now-defunct Art Nerd New York blog. For close to a decade, the Brooklyn-based curator and writer had the idea to create a book filled with her artistic discoveries, and finally, in 2018, after donating a kidney to a friend and grieving the passing of her father, she decided to make the project, which she fondly called, “a bright spot that got me through a dark time,” a reality.

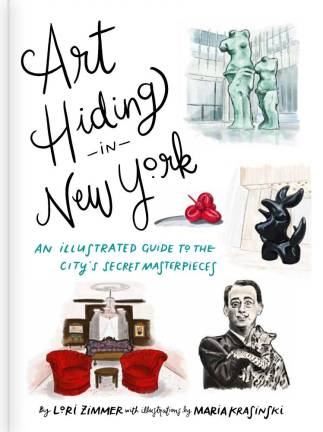

A Buffalo native, Zimmer collaborated with her childhood friend, Maria Krasinski, on “Art Hiding in New York: An Illustrated Guide to the City’s Secret Masterpieces,” which was published in September. Each piece referenced is accompanied by interesting bits of its history as well as a vivid illustration that Krasinski drew with a digital pen and iPad while sitting in front of it. Chapters such as “Surprising Spots” include the windows at Bergdorf that can take up to six years to plan, and the murals at the Carlton Arms Hotel painted by starving artists who worked there in the 1980s. The pages dedicated to “Dine Amongst the Masters” give readers a glimpse into iconic works such as the Maxfield Parrish painting at the King Cole Bar at the St. Regis, the upscale watering hole where the Bloody Mary was first introduced to New York in 1934.

This must-have art resource for the coffee-table book collection of every New Yorker and tourist alike is currently on its second print run after selling out on Amazon and Target during the holidays. And for Zimmer, the timing of the pandemic with the book’s release was surreal because she’s once more found herself with the time to explore its subjects. “It’s funny because I’m sort of in that position again now, 10 years later,” she said. During the pandemic, she has been revisiting all the places in the book, getting a coffee at Caffé Reggio’s outdoor space and watching passersby in Times Square react to the secret sound installation coming from the subway grates.

Let’s start with the first chapter, “Surprising Spots,” where you include pieces by Keith Haring that are in places like an abandoned handball court and St. John the Divine.

I’ve been lucky enough to know some people who were his roommates and artists who worked him, so I got to hear a lot of stories. One reason I wanted to put so much of him in the book was because he was also an activist and really gave back to the community. The Crack is Wack mural he did because the crack epidemic was raging in New York at the time and he wanted to draw attention to it with his star power. No one plays handball on that court [on 128th and Second] anymore, so people go and appreciate it. And St. John the Divine, that piece that he did, there’s nine of them in the world — I actually saw one two summers ago in a church in Paris — all of his other stuff is pretty energetic, fun and buzzy, and that one felt kind of somber to me. And it was one of the last things he ever made. And I think he was just realizing that he was going to die soon and it’s a connection to religion.

In your dining chapter, you talk about Bemelmans Bar at the Carlyle. I found part about restoring the mural by using Wonder Bread to absorb the nicotine buildup so interesting. How did you discover that fact?

It was in a New York Times article, actually. A lot of the places in the book, especially all the dining ones, are places I had always aspired to go to, but when I worked for the gallery, I couldn’t afford it, and now I’m older and I can. At a couple of them, I would talk to the bartenders and find out stories and one of them at Bemelmans was like, “You have to read the article about the conservation of the walls.”

Another place I was happy to see mentioned is Caffé Reggio. When my dad came to New York in 1968, he would hang out there with his friends. Is that really where espresso was first introduced to the city?

That’s what they claim and I found some old New York Times’ article that claimed it too. I love Café Reggio; it’s one of the first places I was taken to in New York as a teenager by my friend’s uncle. And I didn’t know the name of it and had no idea where it was. When I came back— I interned here when I was 19 at Paper magazine — I remember I was walking around and found it. Anyone who visits me, I take them there. Also, I find it amazing that you can sit on a bench that was owned by the de’ Medici family. It’s there for you. You don’t have to know anything about art, you just have to like coffee or desserts. I went the other day; I’m glad to see they have a big outdoor space. I try to get a coffee from there every so often.

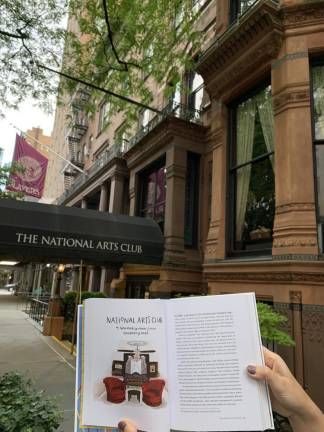

My cousin is a sous chef at the National Arts Club. I love the history you wrote about it, especially the part about it being inclusive of women so long ago.

A lot of these old arts clubs wouldn’t let women in because they thought we were just to be subservient, but not the National Arts Club. I love that. I’m not a member, but I’ve had friends who were members, so I’ve been lucky enough to eat there and go there for different events. It’s just ... how could you not be inspired?

You talked about subway art in the book as well. What’s your favorite piece?

The thing that I always bring people to is a sound installation, Christopher Janney’s REACH at the Herald Square station. That one, for me, is really personal because it was 1999, and I was a sophomore in college. And I was interning at Paper, but I lived in Philadelphia [as a student at Drexel University] and would commute here on New Jersey Transit and then I would sleep over at my friend’s dorm to do two days of this internship. And I was standing on the platform and I saw someone reach up and I heard this marimba sound, and it was this sound installation. He changes the sounds, I guess, every couple of years. It just looks like a utilitarian duct or heating vent, but really, it’s a piece. That kind of changed my life a little bit because I was like, “In this city, art is for people riding the subway. They’re giving everybody art.” And then, when I moved back here in 2005, I was psyched that it still worked. I just assumed it would have been broken. It fascinates me that it’s there.

To learn more about Lori’s book, visit https://www.runningpress.com/titles/lori-zimmer/art-hiding-in-new-york/9780762471003/